Reviving the Zionist Dream

Reviving the Zionist Dream

April 16, 2010

Negev Development & Community Programs

A heavy haze thickened the air around the small cluster of prefabricated rectangular buildings, the result of a hot Negev wind forming swirls of dust along the dirt paths of the village. The normally blazing desert sun on this day glowed only dimly from behind a dusty veil.

A heavy haze thickened the air around the small cluster of prefabricated rectangular buildings, the result of a hot Negev wind forming swirls of dust along the dirt paths of the village. The normally blazing desert sun on this day glowed only dimly from behind a dusty veil.

The chamsin, or dust storm, that occasionally drowns Israel’s southern region under waves of dust particles from North Africa rendered the picturesque student village on the outskirts of Dimona uncharacteristically deserted on a recent spring day.

None of the usual boisterous singing filled the community clubhouse; the central courtyard, paved with pale-pink rough-cut stones, was devoid of students lounging and laughing; no pensive young Israeli stood under the wooden gazebo at the edge of the village, which overlooks the vast expanse of rolling desert hills.

“This is not a good day to tour the Negev,” said Dany Gliksberg, a rugged and handsome Israeli tanned by the desert sun and dressed in a loose-fitting T-shirt and sandals.

“Usually the village is alive with activity, and the view here is stunning. It’s difficult after living in a place like this for three years to go back to Tel Aviv. The beauty of the desert, the peace and quiet, the closeness to nature — there’s nothing like it anywhere in Israel.”

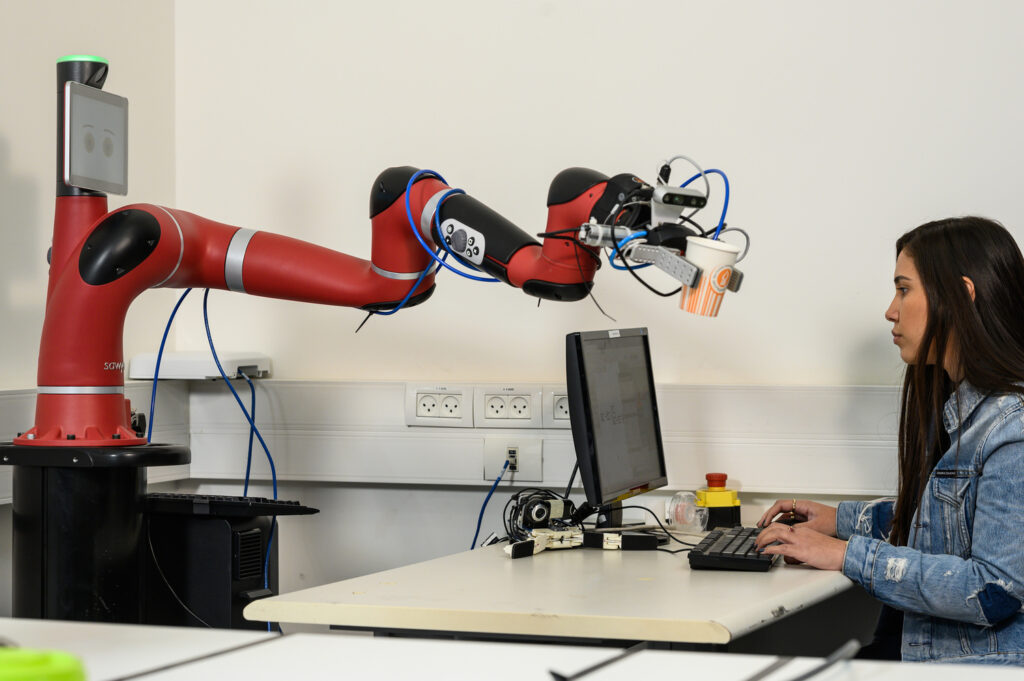

Einav Saruk is a student at the Ayalim village in Yerucham. The pioneering Israeli youth movement is being touted as the hardy new transformation of old-school Zionism. |

Gliksberg is one of the founding members of a pioneering Israeli youth movement called Ayalim, which is being touted as the hardy new transformation of old-school Zionism. Students live and work together to revive the Zionist values of community building, entrepreneurship, connection to the physical land — all the while building pride in Israel as a Jewish state by constructing villages in Israel’s under-populated peripheral regions.

The students live low-cost in the housing that they either build or renovate in the middle of depressed communities and are required to do volunteer work in the communities — tutoring Bedouin children, for example. The goal is to create bonds in hope that once the students graduate, they will build their own futures — and the future of Israel — in the Negev and Galilee.

“Five years ago, if you approached a young guy in Tel Aviv and told him to go live in Dimona [in the Negev], he would tell you you’re crazy,” Gliksberg, 31, said. He grew up in Jerusalem and once had aspirations of becoming a doctor but now feels that he is fulfilling a different, and much bigger, kind of dream.

“Today, for every open space in one of our villages, we have 10 students waiting in line,” he continued. “Israelis today want to be a part of something larger than themselves. There is a real desire and excitement in our generation to be a part of developing the Negev.

“Past generations had clear missions,” Gliksberg said. “They worked hard and sacrificed to build Israel and defend it. Our generation is somewhat lost because after the army, there is no framework for young people to give back to the country. So the perception is that we don’t care about Israel, we’re not patriotic, all we care about is traveling and making money, and ourselves.

“But it’s not true. Ayalim is proving that. Our generation’s mission has become clear: to strengthen Israel by developing areas that are underused. We’re reviving the Israeli dream, the Zionist dream, of a strong, united, flourishing country.”

Ayalim was created by a group of young Israeli friends, including Gliksberg, who had just completed their army service. They realized their purpose when, in 2002, their friends Eyal Sorek and his pregnant wife, Yael, were killed in a terrorist attack in their settlement town of Karmei Tzur, in the West Bank.

“Their deaths came to us as a sign that our generation has to fight to keep this country ours,” Gliksberg said, pointing to the immense stretch of desert landscape on both sides of the road where he stood.

Pointing out a tin and corrugated metal Bedouin shantytown in the distance, he added, “If we don’t develop the Negev and Galilee, we stand to lose these regions as well. These areas are not in dispute, but they are in danger, so we have to do everything we can now to hold on to this land and make good use of it.”

The friends pooled their army discharge grants, money given to soldiers who complete the required Israel Defense Forces service, and used the funds to found Ayalim — Hebrew for deer — in memory of Eyal (male deer) and Yael (female deer). Their first student village, Adiel, was built in 2005 in Ashalim, a town 30 miles south of Beer-Sheva.

Just like the early Zionists, the students built it all themselves, hammering every nail, laying down every stone and painting every wall. The result is now a thriving mini-town that is the heart and headquarters of the movement. Their do-it-yourself attitude, emphasis on hard work and connection to the land remain core features of Ayalim, even as the association has grown in scale and funding.

These days, 90 students enrolled in various universities and colleges in the area live in Adiel. More than 500 students live in 10 other Ayalim villages throughout the Negev and Galilee.

Each village has its own unique character: Adiel is a beautiful, sand-colored outpost of permanent buildings surrounding a neatly landscaped courtyard with gardens, palm trees and smooth walkways. The urban village in Dimona consists of renovated apartment units scattered throughout six buildings in the one of the southern city’s toughest neighborhoods.

These student enclaves share a purpose beyond simply drawing young Israelis from the overpopulated center of Israel to the poorer, less developed southern and northern regions. Ayalim’s mission is to harvest this new generation’s energy and passion and use it to improve conditions for others who are lacking education, infrastructure, social services, economic opportunity and cultural vibrancy.

Students volunteer 500 hours a year in building the villages and maintaining them, running the family centers they create in each community, mentoring and tutoring inner-city children, teaching extracurricular activities, creating programs for families and the elderly, sparking community initiatives and establishing social services. In exchange, the students, 95 percent of whom study at Ben-Gurion University in Beer-Sheva, receive full scholarships and subsidized housing from Ayalim.

Idan Bin-nun, 28, now a graduate of the program and heading to Columbia University, helped clean up the Dimona neighborhood, building a performance stage for community activities, planting trees and gardens, introducing recycling and helping establish a family center.

“There was trash and rubble covering this entire area,” Bin-nun told a visitor to Dimona, gesturing to the now clean and tidy neighborhood square, the wooden stage at its center. All it took was leading by example, he said, recalling how residents of the rundown complex began to take pride in their neighborhood, picking up trash, watering the gardens, repainting peeling shutters.

At first, Bin-nun’s family, who lives in Jerusalem, couldn’t fathom why a young man would want to live in an impoverished Dimona neighborhood. “But then they came and saw the work we were doing, the effect we’ve had on the kids in the neighborhood, the changes we were effecting, and since then, they’ve been very supportive.”

Once they complete their studies, Ayalim graduates are encouraged to remain in the Negev and Galilee and start businesses that create jobs, build homes that raise property values and become active members of the surrounding communities. The goal is to attract other young Israelis to the region.

Although Bin-nun and his wife, also an Ayalim alumna, are now heading to New York to pursue degrees, he said they plan to return to the Negev. Asked if he is concerned about finding a good job when he gets back, he answered with casual confidence, “If there aren’t jobs, we’ll create them.”

Ayalim has managed, in its eight years of existence, to overcome the steep psychological barrier of living in such development towns as Dimona and Yerucham — so called because of their origins as dumping grounds for the waves of immigrants that flooded Israel during the 1950s, ’70s and ’90s. Israel’s government built cheap public-housing units in undesirable locations far from the bustling center of the country for new immigrants coming from Romania, Persia, Morocco and Russia, and these towns became infamous for high unemployment rates, poverty and crime.

The underdeveloped and resource-starved Negev and Galilee regions comprise 75 percent of Israel’s landmass, yet according to statistics cited by the Or Movement — which also promotes the regions’ development — only 30 percent of Israel’s population lives in those areas. Ayalim’s research cites another statistic: The Negev and Galilee account for only 8 percent of the jobs available in Israel.

The Ayalim students’ passionate and successful hands-on approach to revitalizing these regions — 85 percent of participants stay after graduating from the program — has drawn enthusiastic support and financial backing from the Israeli government, starting with Ariel Sharon’s commitment to the project and continuing with the dedication of numerous other politicians, among them President Shimon Peres and Yerucham Mayor Amram Mitzna.

The movement breathes new life into the late Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s vision of a thriving Negev and is in line with what many Israeli and American politicians are calling the future of Israel.

In 2007, now-former U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice stated that “the future of Israel is in building a strong Israeli state in places like the Negev and Galilee” and not in the West Bank. In March, President Shimon Peres attended the 2010 Negev Conference to discuss the nation’s plans to settle 300,000 people in the south by 2020, and called the Negev the region of the future. At the same conference, KKL-JNF World Chairman Efi Stenzler said, “The Negev is the place for current-day pioneers and lends modern-day meaning to Zionism.”

“We are quite literally the soldiers on the ground doing the government’s work of building up these areas,” Gliksberg said. “Our mission is something that the government, Jewish organizations and philanthropists are quick and happy to get behind.”

The Israeli government, according to Gliksberg, recently committed to help fund the construction of units for 500 more students, which would double the current capacity of Ayalim’s villages. Private philanthropists, including the Merage family from Los Angeles, have been supporters since the movement’s inception and have greatly contributed to its meteoric success. The Jewish Federations of North America and Keren Hayesod have also pledged to raise funds to expand Ayalim’s reach. A 12th village will be built this summer in Karmiel in the Galilee.

Along with its rapid growth and increasing momentum, Ayalim plans to reach out to Jewish communities in the United States and begin to involve young American Jews in this modern-day movement. To that end, AyalimUSA, launched this year, will offer Americans ages 21 to 35 the chance to spend two weeks with Ayalim, touring and volunteering at the existing villages and helping build the new village in Karmiel. The inaugural trip, planned for August, will include a maximum of 15 participants, and the trips will be partially subsidized.

“Baby boomers like me remember summers volunteering at kibbutzim in Israel,” said Larry Weinman, a Los Angeles investment adviser who is spearheading the AyalimUSA effort. “This is an opportunity for young Jews to experience Israel like the old days of Zionism.”

Weinman discovered Ayalim while touring Israel and fell in love with the project’s idealism, energy, Zionism and unifying nature, he said. “It’s inside the green line, it doesn’t divide the community, and it promotes something positive that everyone can agree upon.”

Weinman has been working with Israeli Consul General Jacob Dayan and other Angelenos, including rabbis who were part of a consulate delegation to Israel in November 2009, to develop programs that will encourage American Jews to participate in Ayalim.

In addition to the summer trip, which targets people who have already visited Israel, Ayalim is planning a Los Angeles gala in October and is hoping to create an alternative spring-break trip for University of California students, as well as a semester- and/or year-long student program in partnership with Masa Israel Journey. Applications for the summer trip have already started streaming in, and Weinman is excited by the growing enthusiasm for Ayalim.

“This is the beginning of a great partnership between young Israelis and young American Jews,” he said. “It’s akin to what my generation did years ago to help build Israel, and it’s what this generation has been sorely lacking in its interaction with Israel.”

Gliksberg, who came to Los Angeles in March to speak to various Jewish groups, said he believes that Ayalim’s vigorous, hands-on revival of Zionism can inspire young American Jews in the same way that it has lit a fire under his generation of Israelis.

“When we approached Ben-Gurion University about hosting the first informational meeting for Ayalim, we were told that if 50 students showed up, we should feel lucky,” Gliksberg recalled with an Israeli half-cynical, half-gleeful smile. Instead, “650 people came.”

“People underestimate our generation. The biggest message of Ayalim is that today’s young people are willing to do a lot for thefuture of Israel. And we’re here to lead the way.”