Future of War Will Go with the Flow — Water Promises to be Flash Point

Future of War Will Go with the Flow — Water Promises to be Flash Point

August 3, 2008

Jericho, West Bank — Hussein Mohammed Ali Tayat sighs heavily as he sips thick black coffee from his demitasse cup. “I lost a large portion of my banana crop — millions of shekels — to drought last year. I have 17 family members to support, and the situation is getting worse each summer.”

Tayat, 52, lives in the small Palestinian farming

During the dry summer stretch of June to early October, potable water purchased from

Global population, economic development, industrialization and migration trends are pushing water demand to such unsustainable levels that a 2003 Pentagon study on climate change predicts resource-rich nations will eventually build virtual fortresses around their countries to preserve water resources. Less fortunate nations — especially those with ancient enmities with neighbors — may instigate conflict over access to food, energy or clean water.

A leaked global climate report compiled by the U.S. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change details predictions of rising global temperatures resulting in critical water shortages in

In the here and now, half the world has no access to clean water and more than 2.5 million people die each year because of it, says Aaron Wolf,

“The magnitude of potential destruction is staggering,” Wolf says from his

Do the statistics, studies and situations on the ground foreshadow a future global reality of influential nations strong-arming weaker counterparts into extinction over water control? Will there be wars over water in the future?

The answer depends upon the source.

Conflict over water dates back as far as the Book of Genesis: Attempting to staunch famine in

Historically, trouble over water erupts when a river, lake or stream originates in one place and flows to another. Determining who controls the flow and divvying up usage often necessitates commissions, governing authorities and legal action. And even then, implemented measures often don’t suffice.

Of the top 10 countries the

The

In the 1970s,

And in 1967,

“Some call 1967 a war for water because after it,

After factoring in agriculture use and loss due to poorly maintained pipelines and water pirating, the average Palestinian end-user is left with about 60 liters per day. That’s less than half of the World Health Organization’s minimum standard of 150 liters per person per day.

Does Israel’s control of the aquifers constitute water theft? “That’s propaganda,” says Professor Alon Tal of Israel’s Jacob Blaustein Institute for Desert Research dismisses. “This is a classic case of trans-boundary water sharing and Israel is the downstream user. That is as absurd as claiming that Egypt steals Nile water from Ethiopia.”

Regardless, the divvy is lopsided, a fact Israeli water commission officials put down to greater consumption needs and a pre-existing water use clause in international law. In water negotiation, pre-existing water use laws stipulate a country’s projected future water use based upon pre-existing usage up to the point of talks.

So in the case of

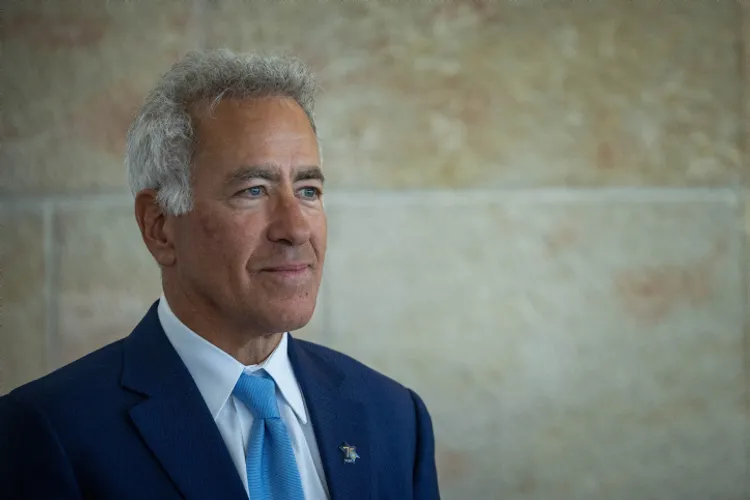

“During negotiations I directed and redirected the focus back to ‘pre-existing use’ which is precedent-setting,” says Noah Kinarty, Oslo II Water Accord architect and water policy adviser to former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. “I told our Arab counterparts: ‘Water recycle and desalination is the future. You want the water I use? I’m not willing to give up my natural resources.’ ”

Dirty politicking? Not at all, claim Israeli policymakers who maintain

“Donor countries offered to fund projects to bring in water and we began a plan of principles and prepared an area for a desalination plant,” says Yosef Dreizin, senior director of

But it stalled, claims an Israeli government source, because “Palestinian leadership is purposely avoiding solutions to keep their own people in the mire. That way they gain global sympathy and support.”

Regardless, while internal factions war for power, water supplies dwindle. Pirate aquifer drilling contaminates freshwater and untreated sewage is at hazardous levels: in March five people died when a collapsed embankment flooded a

The pressing question: Is war on the horizon? And if so, are the implications — based on the

Water researchers, policymakers, negotiators, scientists and environmentalists on both sides of water conflict tend to be in agreement: Tension over water runs high but war on a global front is highly unlikely. These water experts are unique in the tendency to sidestep conflict in favor of compromise.

Of all the Palestinian-Israeli committees established under the umbrella of the 1995 Oslo II Interim Peace Agreement, only the Joint Water Committees continue to meet regularly and cooperate.

“The idea of water wars is sexy and appealing but it’s media hype,” says Yaakov Keidar, the Israeli Foreign Ministry’s deputy director general for

Nader Al Khateeb,

“It took thousands of hours and endless patience to reach an interim peace agreement,” Noah Kinarty says. “But I have endless patience. Because I know peace is better than war. I’ve fought wars and I lost a child to war. Peace is always better.”