Drivers Are As Good As Their Vision

April 4, 2011

Mom and Dad always told you to look both ways before crossing the street, but if Grandma or Grandpa is driving down the road, you’d better look twice. A recently published study by researchers at Israel’s Ben Gurion University concluded drivers 65 and older are half as likely to notice pedestrians and other roadside hazards as drivers in the 21 to 40 age group.

Mom and Dad always told you to look both ways before crossing the street, but if Grandma or Grandpa is driving down the road, you’d better look twice. A recently published study by researchers at Israel’s Ben Gurion University concluded drivers 65 and older are half as likely to notice pedestrians and other roadside hazards as drivers in the 21 to 40 age group.

This is partly due to diminished peripheral vision. But that isn’t the only problem, the study shows: Those 65 and older also are much less likely than younger drivers to pay attention to those pedestrians they do notice, and are slower to react when necessary.

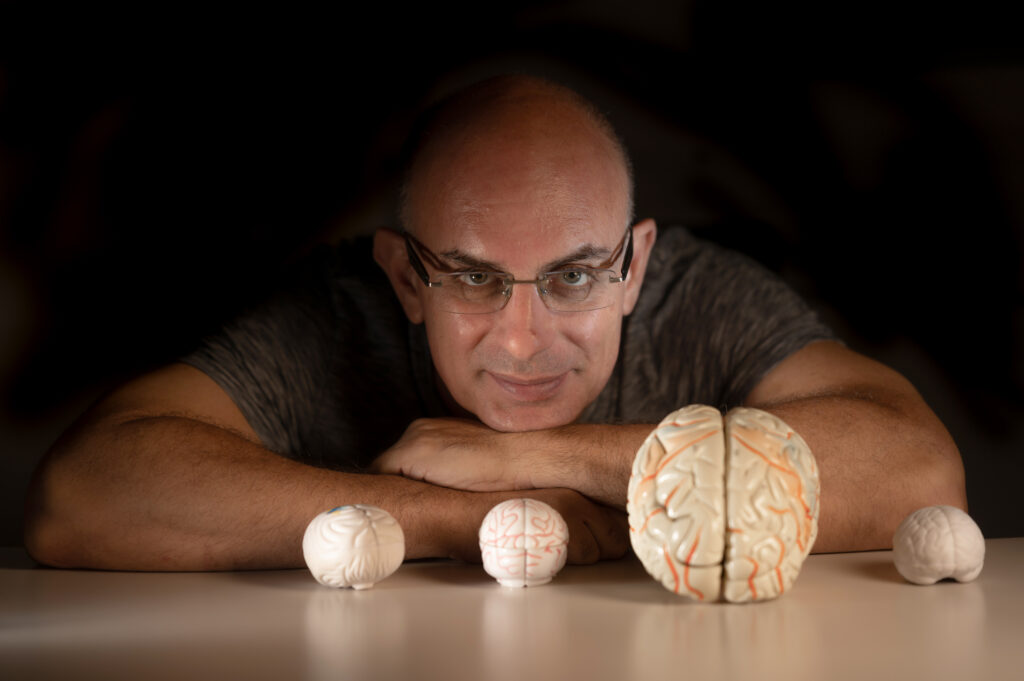

Ben Gurion University (BGU) researcher Tal Oron-Gilad said between 2000 and 2009, older drivers in Israel have been involved in disproportionately more pedestrian-related crashes — even though overall statistics show they crash less than drivers in any other age group. And the problem could get worse.

The 65-and-older population is the fastest-growing demographic group in the Western world, Oron-Gilad said, adding the confluence of these trends is what prompted her and her colleagues at the BGU Department of Industrial Engineering’s Ergonomics Complex and Driving Simulation Laboratory to begin their study two years ago.

Their goal was to determine whether older drivers’ propensity for pedestrian-related crashes stems from problems perceiving the hazard or trouble responding to it. The study involved a group of 20 older experienced drivers and 22 experienced drivers aged 28 to 40. Each took two tests. The first, using videos of drives to measure their reaction times to hazardous pedestrian events, required the participants to press a button when they saw a hazardous situation. The second entailed driving in a traffic simulator using a steering wheel, accelerator and brake pedals to record their responses.

Older Drivers Safer Drivers?

The results indicated older drivers have difficulty seeing pedestrians who are outside the center of their useful field of view and are slow to react once they do see. Thus, for example, they had difficulty noticing pedestrians about half the time in the movies and hit the brakes in the driving simulator half as often as the younger drivers in response to pedestrians on sidewalks and road shoulders, the researchers found.

“These findings strengthen the notion that elderly drivers, shown to have a narrower useful field of view, may also be limited in their ability to detect hazards, particularly when outside the center of their view,” Oron-Gilad said. “Authorities should be aware of these limitations and increase elderly drivers’ awareness of pedestrians by posting traffic signs or dedicated lane marks that inform them of potential upcoming hazards.”

Additionally, “just like they go for a physical, (older drivers) should have an environment where they can assess all their abilities properly,” she said. This does not exist today but could take the form of a government-run facility that tests not only driving but also eye-pattern scanning, she suggested. “There are no good tools right now for authorities to assess whether an elderly driver should be permitted to continue to drive or not,” Oron-Gilad said.

To be sure, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) data shows drivers 65 and older are less likely to be involved in a fatal crash than drivers 21 to 64 years old.

The last time NHTSA compiled such statistics, 2001-2005, the fatal-crash rate for over-65 drivers was 22.2 incidents per 100,000 licensed drivers, versus 22.7 per 100,000 for the younger age group. This was in spite of faster growth in the population of 65-and-older licensed drivers compared with the population growth rate of licensed drivers 21-64 years old –– 5.4 and 5 percent respectively. Moreover, it is the case that older drivers are aware of their limitations in general and drive 20 percent slower than younger drivers to compensate. However, Oron-Gilad said, “that’s not enough.”

Vision Tests Need Improvement

Cynthia Owsley, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, sees another potential problem — the common vision test for granting driver licenses may be insufficient. “When departments of motor vehicles licensing divisions implemented vision screening many decades ago, they were using the visual acuity test to establish some minimal level of vision to ensure that people they licensed were going to be safe on the road,” Owsley said.

But visual acuity, or the size of letters a person can read at a given distance, “really has very little to do with driver safety,” she said. “It is important for reading signage down the road, but it actually is a very poor predictor of who is going to be crashing in some subsequent years. Other sorts of visual skills are probably going to be more useful in identifying adults who are more likely to crash.”

Accordingly, Owsley’s research group at UAB two years ago began a study, funded by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, comprising drivers age 70 and older in north-central Alabama. The drivers are undergoing a variety of vision and cognitive assessments, with the goal of devising better tests for DMVs to use. It is this age group that has the highest prevalence of vision problems, Owsley said.

Besides visual-acuity screening, the tests cover peripheral vision, contrast sensitivity, visual spatial skills and visual information processing speed, among other attributes and capabilities. In addition, after those tests are taken, the researchers are following the participants’ driving and crash records for three years, to correlate their test results with motor-vehicle collision involvement. The study is still in enrollment — 1,700 of a target group of 2,000 are already included — and Owsley anticipates having preliminary data available three years from now, when “we’ll be able to inform policy makers, the public (and) the scientific community (about) which of these vision tests are really the most useful for identifying crash-prone drivers.”

Cars Part Of Solution

Of course, it’s not only older drivers who crash into pedestrians. “We’re all suffering from cognitive overload, inappropriate allocation of attention,” said Bryan Reimer, research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s AgeLab in Cambridge, Mass., and associate director of the New England University Transportation Center. His research covers the causes and effects of such mental multitasking by drivers, and ways to deal with it.

“Drivers tend to look straight ahead but not actually perceive what’s going on,” perhaps because they’re more focused on their cell-phone conversations or thoughts of work or chores. And “there’s no age effect” among healthy adults, Reimer said. “The 20-year-olds are no better than the 60-year-olds at managing these types of demands.”

But the health of the driver is an important factor, he said. “So, the perfectly healthy 75-year-old is far more capable of driving a car than a 60-year-old suffering from Type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease and taking medication to control that,” which would affect “cognition, decision making, speed of processing.” Reimer says he believes the best solution to this problem will be “applying feedback in the vehicle to try to slowly and very subtly nudge behavior into a slightly better place. And I say slowly because if you do anything very quickly you actually can distract the driver, pulling (his) attention away from the road.”

In a paper published in 2009, he and colleagues at the AgeLab described an AwareCar concept that would “detect driver state (fatigue or stress); display that information to the driver to improve the driver’s situational awareness in relation to road conditions and their own ‘normal’ driving behaviors; and offer in vehicle systems to refresh the driver, thereby improving performance and safety.”

Automakers such as Volvo already offer a slow-speed pedestrian-detection system in their cars. The system alerts the driver to impending accidents and stop the vehicle automatically at the last moment if there is no response. But these are only an incremental development, Reimer said. “Driver training technology in the vehicle is a huge and growing area that needs considerable development.”

Pedestrian Role

Certainly, pedestrians themselves must remain alert. But they suffer from the same lack of attentiveness as drivers, Reimer said. He describes people who are so engaged in cell-phone conversations they wander into traffic without looking. “It’s the same phenomenon. What’s going on here is we have a real fallout in situational awareness,” he said.

“That’s the other part of the equation,” Oron-Gilad said. In fact, she said, she and her BGU colleagues are now working on another study involving pedestrians in a different simulator facility to examine their perceptions of risk from oncoming cars. It compares the different behaviors of adults and children, and is slated to be completed this summer. But, she said, none of the BGU studies is meant to convey the idea that older drivers as a group should be prohibited from driving. They are instead stating that authorities should find ways to help the elderly to be better drivers.