Come Stand In My Place

November 2, 2009

On Saturday, May 22, 1948, a group of men clustered in front of Cafe Ta’amon in Jerusalem. Most noticeable was a stocky man of about 40, with a cigarette in his mouth and a black beret on his bald head.

On Saturday, May 22, 1948, a group of men clustered in front of Cafe Ta’amon in Jerusalem. Most noticeable was a stocky man of about 40, with a cigarette in his mouth and a black beret on his bald head.

On his left arm was tattooed the number 43057 and next to it a Star of David, but his shirt sleeve covered that. His name was Eliezer Greenboim.

The group had been conscripted a week earlier into the Haganah militia, the day after the declaration of the State of Israel. Menahem Richman, their commander, met them for the first time that day, shortly before they were sent out as reinforcements to Kibbutz Ramat Rachel, which was under attack.

Greenboim told Richman about his combat experience in the Spanish Civil War, in which he had fought for the Republicans, but did not mention his political views (Greenboim had been a communist since his youth), his family connections (he was the interior minister’s son) or the fact that he had been inducted only thanks to David Ben-Gurion’s personal intervention. In the afternoon, when their briefing had ended, they moved in an armored vehicle toward the kibbutz, and soon came under heavy fire. A shell hit the vehicle, and Richman and 10 of his men were killed. Greenboim was wounded by shrapnel in his jaw, took cover and returned fire.

In the afternoon, when their briefing had ended, they moved in an armored vehicle toward the kibbutz, and soon came under heavy fire. A shell hit the vehicle, and Richman and 10 of his men were killed. Greenboim was wounded by shrapnel in his jaw, took cover and returned fire.

Someone behind shouted that they had to retreat, but Greenboim kept crawling forward, a machine gun in his hand. When he stood up, a bullet hit him and he too was killed.

His girlfriend, Steffa Rosenzweig, a Holocaust survivor, chose not to attend his funeral: She swallowed some sleeping pills and died in her apartment in Jerusalem.

Rumors swirled around the death of Eliezer Greenboim, also known as Itcha, Albert, Azriel and Leon Berger. It was said that someone had taken advantage of the battle conditions to shoot him from behind – that he was killed in order to settle an account for his deeds at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where Greenboim had been a cruel and terrible kapo.

It was said that someone had taken advantage of the battle conditions to shoot him from behind – that he was killed in order to settle an account for his deeds at Auschwitz-Birkenau, where Greenboim had been a cruel and terrible kapo.

In his new, hefty book Who Are You, Leon Berger? (Resling Press; in Hebrew), historian Tuvia Friling has difficulty solving the mystery surrounding the cause of his death, and ends up leaving his readers with three possibilities:

First, that Greenboim was indeed killed by the enemy in battle; second, that he was shot in the back by someone on his side who knew his past; third, that he behaved in battle in a reckless and suicidal way because he had nothing left to live for. Friling tends to accept the latter possibility.

“I think that this brilliant and intelligent fellow went knowingly to his death,” he says. “It’s most likely in my opinion that at a certain moment, he realized this was a ‘golden opportunity’ to end the story of his life, especially as he knew it would endow him with a heroic aura.”

The impression emerging from his book is that Friling is presenting a detailed defense brief for the man and, at the very least, a testimony to his character. Nonetheless, the book is not a comprehensive biography of Eliezer Greenboim.

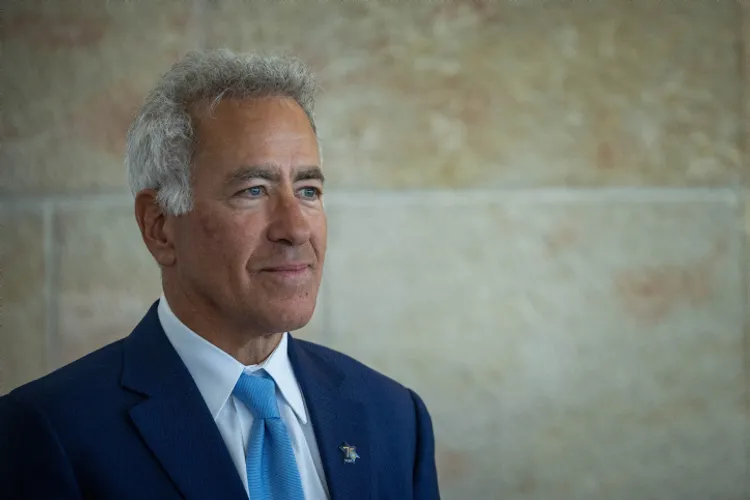

“I didn’t see fit to start with the story of his childhood,” says Friling, a senior researcher at the Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

“There is a biography that Roman Frister wrote about his father, Yitzhak Greenboim [Without Compromise; 1987], which also focused on Eliezer, the communist son, and constituted a kind of introduction to the story of someone who diverged from his father’s path and became a man of the underground, each time in a different context: once in Poland, then in Paris, then in Spain and again in France.

I was interested in that part of young Eliezer’s life, when he made a conscious choice to take that path. I delve into that part. I was interested in the period when he became a communist, in what led to his sentence at the age of 19 to four and a half years in Lenczyce Prison, near Lodz.”

In the 1990s, when Friling was working on his book Arrows in the Dark: David Ben-Gurion, the Yishuv Leadership and Rescue Attempts during the Holocaust (published in Hebrew in 1998, and in English in 2005), he also wrote about the activity of Yitzhak Greenboim, a member of the Jewish Agency executive and head of its committee for the rescue of Europe’s Jews.

Before immigrating to Palestine in the early 1930s, Greenboim was one of the most important leaders of the Zionist movement in Eastern Europe in general and in Poland in particular. He supported the separation of religion and state, and aspired to the establishment of a secular Jewish society in Palestine.

Friling found Yitzhak Greenboim so intriguing that he considered writing a political biography of him, before he stumbled upon the terrible story of his son Eliezer-Itcha.

The resulting work is not only about his life, the historian explains, but also reflects “the way we as a society dealt with the story of Jewish leadership in the Holocaust, which also included the roles of Judenrat and kapos.”

To read the rest of this article visit Haaretz here.