Breaches in Blood-brain Barrier Might Lead to Later Psychiatric Illness

Breaches in Blood-brain Barrier Might Lead to Later Psychiatric Illness

April 16, 2010

In 2006, Matthew Stern, a 30-year-old soldier from Houston, Texas, was knocked unconscious for nearly four minutes when his military vehicle hit an improvised explosive device (IED) in Iraq.

“When I woke up in the hospital, the doctor said I had a bruise on my brain and we’d have to wait and see what the long term effects would be,” Stern says.

Since the blast, he has developed epilepsy as well as dizziness, sleep problems, and recurring headaches and seizures. He expects to be on medication to control the seizures for the rest of his life.

Researchers have learned a lot about the ways traumatic brain injury (TBI) may bring about widespread damage to the brain. But a new hypothesis suggests that a TBI like Stern’s, as well as other types of injuries and infections, may lead to breaches in the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a layer of tightly packed cells that separates circulating blood from cerebrospinal fluid.

Researchers think those breaches may alter molecular signaling pathways between the BBB and the brain that ultimately result in disorders like epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and some psychiatric illnesses.

A new focus on the blood-brain barrier

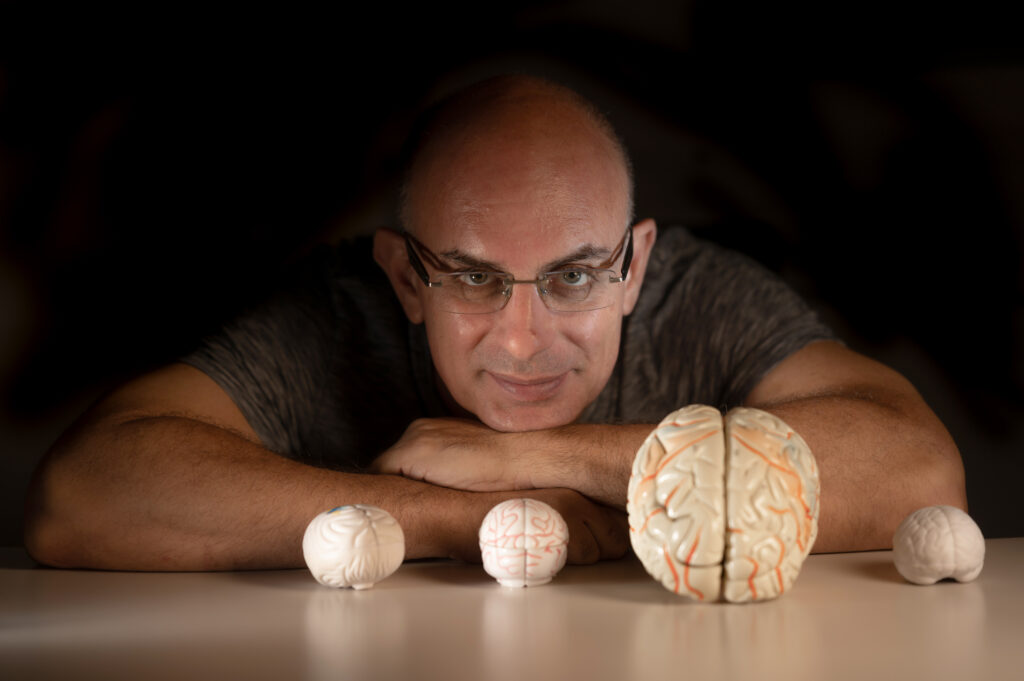

In the past 10 years, there has been growing interest in understanding the blood-brain barrier – but that focus has been limited to finding ways around it to deliver targeted drug treatments for various diseases. But clinical observations coupled with study of animal models have led Alon Friedman, a neuroscientist at the Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, to hypothesize that the blood-brain barrier may be a gateway to psychiatric illness.

In a paper published in the 2009 issue of Cardiovascular Psychiatry and Neurology, Friedman argues that injury and illness can result in abnormal blood-brain barrier function—leading to neuroinflammation and, ultimately, the development of brain pathophysiologies later on in life.

“The BBB is a very complex structure,” Friedman says. “And you can see an opening or breakdown of this barrier in many different neurological disorders.” Friedman has noted that more than half of people with TBI show some sort of problem with the BBB. In some patients, the disruption fixes itself within days. But those with a more delayed recovery, he noted, were the ones more likely to develop epilepsy or other disorders later on.

With the ability to look more closely at the BBB, the idea that it may play an important role in the development of psychiatric illness is catching on.

“If you had asked clinicians ten years ago in which brain disorders do you see BBB damage, they would have said, ‘Possibly multiple sclerosis and certainly tumors, but that’s it,'” says Joan Abbott, a professor of neuroscience at King’s College London.

“Now we can list something like thirty five diseases where the barrier is not performing its normal regulatory functions. They all show some degree of blood-brain barrier disturbance. And if we could understand what the blood-brain barrier is doing in all those diseases, it could lead to new treatments.”

A more sophisticated view of the BBB and disease

Advances in technology that allow researchers to look at cells around the brain at the cellular and molecular levels suggest the blood-brain barrier is a lot more than just a simple barrier.

“The BBB is a complex, regulatory interface with its own rules in place,” says William Banks, a researcher at Saint Louis University. “It makes judgment calls about what can get in to the brain and what gets out, sure. But it’s not a brick wall. It keeps things out but it is also secreting things and cross-talking to cells in the brain and the blood. We’re only beginning to understand it all and what it means for the pathophysiology of central nervous system disease.”

Friedman thinks that an injury like Stern’s, as well as other sorts or injury or even a viral infection, can lead to breakdown in BBB function, and that disruption of normal BBB cross-talk leads to neuroinflammation—and, over time, psychiatric disease. In studies opening the BBB chemically in animal models, Friedman and colleagues tracked the molecular processes that occurred after the breach.

By attacking the BBB chemically, the group was localize the damage to blood vessels and not surrounding neurons or glial cells. And they found that the damage did indeed result in neuroinflammation and later neurodegeneration. Further studies have led him to hypothesize that location-specific breaches resulted in different neuropsychiatric disorders.

“We think breaches result in location-specific disorders,” he says. “If the barrier is opened near movement-related areas of the brain, you see epilepsy. If near an area involved with emotional response, you may see depression or disturbed emotional response. If it’s in the front area of the brain responsible for judgment, we may see problems with decision making.”

A chicken-and-egg problem

But is the injury causing inflammation leading to disease? Or is the disease itself rather causing that inflammation in addition to the injury? A true causal relationship is difficult to determine.

“In Alzheimer’s disease, we have noticed that there are some changes to the very smallest blood vessels around the brain,” says Daniel Perl, a professor of pathology, psychiatry, and neurosciences at Mount Sinai Medical Center. “And we know that some neuroinflammatory markers are present around these blood vessels, suggesting they may be a mechanism. But at this point, it’s unclear what exactly is going on.”

Banks says the buildup of amyloid-beta plaques, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, makes it clear that the BBB is not doing its job. “The BBB may still be intact here,” he says. “Yet there’s still dysfunction because all that extra amyloid-beta is not getting pumped out of the brain the way it should be.”

The question still needs careful study, Abbot says. “We can detect the blood-brain barrier is not doing its job but we’re unsure whether the disease results in inflammation and all local cells, including blood-brain barrier cells, are affected or, alternatively, that the inflammation in the barrier’s blood vessels causes them to regulate less efficiently so the brain side suffers,” she says. “It’s very difficult to determine which is chicken and which is egg.”

Next steps

Abbott, Perl and Banks say that Friedman’s hypothesis has merit, but there’s still a lot of study needed before it could be proved. Researchers need to collect more information about BBB dysfunction when trauma patients are initially treated. To date, there is no quick and easy diagnostic tool for doing so.

Abbott says clinicians need to create a diagnostic panel to help understand the pathophysiology better —having several potential measures of faulty BBB regulation including blood, protein, and cytokine analyses as well as neuroimaging and electroencephalography results can help physicians establish better baselines. But she’s hopeful that this hypothesis may open up some new treatment possibilities for disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression.

“These conditions are currently hard to treat with existing drugs and approaches: We’re treating them as a nerve cell connectivity or neurochemistry problems,” she says. “But if Friedman is right and they share some degree of blood brain barrier dysregulation, we could aim to correct the barrier function so the brain could go back to regulating itself. The neurochemistry might then sort itself out on its own or with less medication.”

Friedman hopes the hypothesis will inspire work that eventually leads to drug treatments to close potential breaches soon after the initial injury or illness, before downstream molecular processes set the stage for later psychiatric disorders.

Stern, now out of the Army on a medical discharge, says he wishes there was something doctors could have done to prevent his epilepsy after the IED blast, and he does worry about developing other neurological problems in the future. Still, he is stoic.

“I’ve learned to live with my seizures just going day by day,” he says. “If there’s more to come, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s or whatever, I’ll learn to live with it the same way.”

To learn more about Dr. Friedman’s research, see the cover story of the Spring 2009 Impact, page 14.