BGU Students Learn the Language of Medicine

BGU Students Learn the Language of Medicine

February 17, 2011

Sitting in a circle in a Beersheba classroom, 14 third-year medical students transported themselves mentally to a clinic in Washington Heights, New York City, where they were to play doctor to “Mr. Castro,” a predominantly Spanish speaker experiencing “diffuse abdominal pain,” malaise and vomiting – with four kilograms of weight loss and elevated levels of lead in his blood.

The first student to take the doctor’s chair, Jonathan Drew, was able to find out that the patient was from the Dominican Republic, but he got little information from him beside the fact that he has “no job,” he lives in a fourroom apartment with his daughter’s family and he plays guitar in Hudson River Park.

“Is anyone else sick like you?” Drew asked. “Yes I sick, not good here,” responded the actor playing Castro, who repeatedly referred to his abdominal pain as simply “fire.”

Drew and his peers, third-year students at Ben-Gurion University’s Medical School for International Health, were partaking in a cross-cultural workshop to prepare for the intense set of clinical rotations they will embark upon during their fourth and final year as medical students. Ben-Gurion’s program is one of three English-speaking medical school programs here.

The school primarily admits Americans and Canadians, and operates in collaboration with Columbia University in New York, selecting about 42 students for each class. After three years of studying and doing clinical rotations here, the students have the opportunity to expand their education elsewhere – serving thus far in two-month internships in Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Peru, Sri Lanka, Uganda, Vietnam and Nepal.

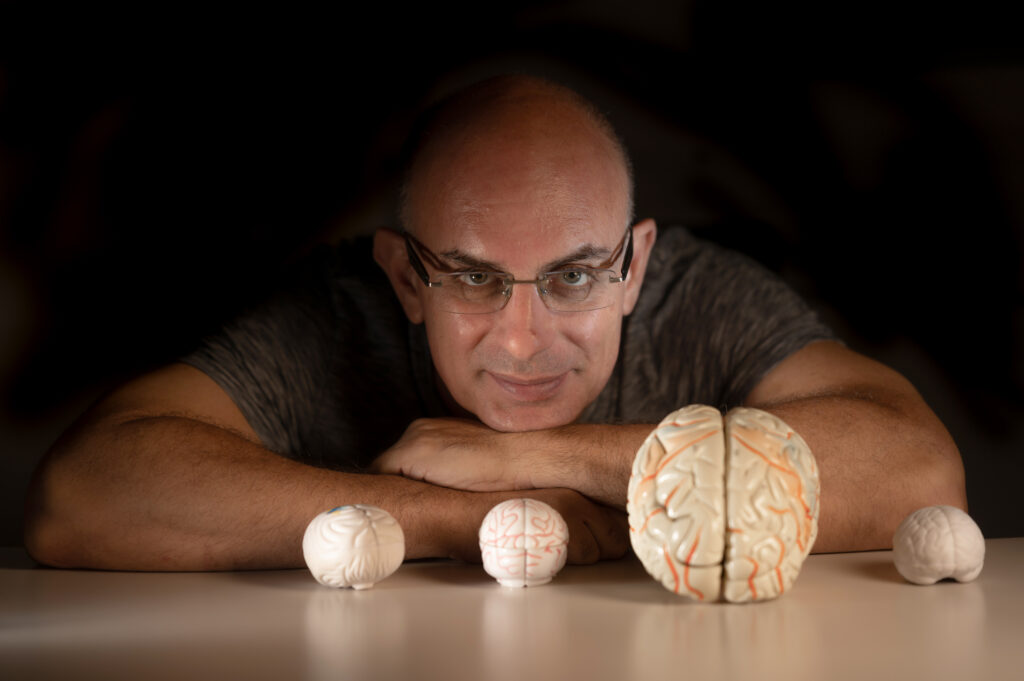

“Our students who come to us say they looked around the world and they couldn’t find anything else,” said Mark Clarfield, Israel director of the Medical School for International Health and a professor of geriatrics at BGU’s Faculty of Health Sciences. “A lot of medical schools now have international tracks, so if a student is interested he could go abroad. But the entire curriculum is not geared toward international health.”

Here, he said, students find “things you wouldn’t get at Harvard,” such as courses about water purity, malaria and medical anthropology.

His students, like Drew, 26, from North Carolina, testified to this. “The reason why I liked this program over others is actually being here in this country and the different perspective of living in this culture that’s different.”

Rory Spiegel, 29, formerly a physical therapist who was raised in a home that believed in both homeopathic and “inter-dimensional” medicine, agreed. “I always found Western medicine kind of alienating,” he said. “I was really interested in this program because of the human nature of it. I thought in some ways it would delay that loss of soul that comes with studying medicine.”

Beginning this year, however, the fourth-year students’ clinical rotation choices have become at least temporarily limited, because the US Department of Education suddenly stipulated that citizens who receive US government-guaranteed student loans can no longer attend internship programs outside the US and Israel. The students receiving loans are still able to do rotations among underserved US and Israeli populations, with opportunities here that Clarfield still deems “pretty exotic” in the Beduin, Druse, haredi and Ethiopian communities. Canadian students and those not receiving loans can continue to travel elsewhere.

“There’s cautious optimism that it will be better next year,” Drew said, noting that about 75 percent of his class would be affected.

But wherever they end up next year, the students were able to learn from their experiences that day, which began with a morning meeting, led by course academic coordinator Dr. Agneta Golan, in which students presented objects or traditions from their own cultures.

One student, Shelly Theobald, 28, presented a tiny tattoo of a cross on her forearm. “I had a hard time because I don’t exist in a culture,” she told The Jerusalem Post. “I grew up in a tribe in Papua New Guinea but my parents were American. I basically have no culture. So this was something that I got – something they do all over their bodies, in random designs. It’s something all of us kids got when we left the tribe – they used to do it with charcoal and thorns but now they use battery acid. I got a cross because I am a Christian. No matter where I’d go or what culture I was surrounded by, religion has always been the same for me. It reminds me of my past.”

Though she left Papua New Guinea at 18 to return to the US for college, like so many of the other students, Theobald spent time traveling, including working extensively with an AIDS organization in Uganda.

Two other lectures followed that morning, “Language as a Cultural Barrier” by Prof. Miriam Shlesinger, head of the Language Policy Research Center at Bar-Ilan University’s Department of Translation and Interpreting, and a seminar called “Truth Telling: A Cross-Cultural Odyssey,” with Prof. Ora Paltiel from the Hebrew University.

Paltiel spoke about her experience as a young doctor when she was once too blunt with a patient, who ultimately refused to come back for treatment and subsequently died from a tumor. Stressing how important it is to take the patient’s culture into account when delivering a diagnosis, Paltiel said, “In American medicine, autonomy takes precedence over everything and in other places beneficence takes precedence over autonomy.”

This warning is something the students would need to heed a couple hours later, when they’d act as doctors to patients from very diverse backgrounds, patients who would later provide them with feedback about how they did after getting through 45 minutes of often gritty conversations that sometimes would lead nowhere.

“This is the only opportunity in your lifetime that a patient is telling you how he feels about you,” Golan told one of the groups. “They might sue you, but they never tell you how they feel in the chair.”

BACK IN the classroom, Drew handed over his doctor position to Tali Okrent, 28, who determined that Castro had been sick for four or five weeks, and while his apartment building was “old,” the paint on the walls didn’t seem to be the cause of his lead poisoning.

Okrent decided to take Clarfield’s advice and follow a protocol they had learned earlier that day from Golan, using the “CHAT” method – or cultural and health belief assessment tools – which includes simple questions like how do you think your disease started, what does the disease do to you, how bad do you think your illness is and what have you done to treat your illness? Golan had instructed the students to use these questions to improve communication and “negotiate a treatment plan,” along with reading body language and finding a way “to politely enter somebody else’s culture.”

Okrent chose to ask, “Why do you think you started to feel sick?” and received only the frustrating response, “I not doctor.” But after a few more questions, the man identified that his feeling of “fire” had moved from his legs to his stomach after he had attempted to treat the leg fire with a powder from a local pharmacy.

“Another student, Liz Morgan, 26, was able to determine that friends of his have also used this powder but are not sick as far as he knows.

“I can give you something else instead of the powder for the fire,” she said. But she and the other students still struggled to communicate that he must use a new “powder” that they would provide to cure his athlete’s foot.

“You knew he had lead poisoning,” Clarfield said to them. “How do we help this poor gentleman? It’s not hard medically, but it’s very hard linguistically and culturally. He might have a PhD or a second grade education – he just doesn’t speak English.”

Clarfield instructed them to make compromises by doing things like “use the little Spanish you have – fake it,” “dumb down your English” and use key words, like “powder, no good. Good for the feet, not good for the stomach.”

Meanwhile, the actor, Miguel Orbach, who has been doing medical acting for more than six years, suggested that the students try speaking with their hands.

“We’re lucky here because this particular patient seems very respectful of you doctors,” Clarfield said. “He thinks you know everything. This means he’ll be very compliant.”

The two other patients were not nearly as cooperative, though their command of the English language was not a problem. The students were introduced to a young man named Rick, to whom they had to deliver a positive diagnosis for HIV.

“Your results came back and your white cell blood counts are low,” said the first student, Prakash Ganesh, 28. “Whatever that means,” Rick responded.

After struggling for some moments to tell Rick the truth, Ganesh finally said, “We ran some tests and we found out you have HIV.” But the patient refused to accept the results and even became aggressive.

Since Rick clearly wasn’t going to cooperate with Ganesh, Frayda Kresch, 25, took over. But as soon as she attempted to speak with him about his diagnosis, he resorted to flirting with her.

Aptly acknowledging his compliment but reinforcing her role as a doctor, Kresch quickly went on to explain how “HIV is a very different disease than what it was 20 years ago.” But Rick just responded, “The girls I go out with are from Tel Aviv, you know. And if I pick up a tourist here or there, I’m talking about quality girls. You can tell.”

Only when Kresch decided to ask him what would possibly get him to listen to her did the patient become slightly more willing to accept and discuss his diagnosis – his answer, after nearly a minute of silence: “Maybe if my holistic doctor came.”

The medical school professors in the room were very impressed by Kresch’s patience.

“You asked him what would convince you, and there was total silence for a while,” said Shimon Glick, one of the instructors and professor emeritus at the school. “Most people who interview are afraid of silence. But in a way it forces the other person to react and you don’t have to do anything.”

Kresch explained that after observing Ganesh handle the patient, her goals immediately became to make sure the prognosis seemed positive and “trying to figure out what his bible is” – in the end, his homeopathic doctor.

Meanwhile, Ganesh said, “I felt really uncomfortable breaking the news that he had HIV. I didn’t know how to throw that out there.” But he added, “The funny thing is I used to work with HIV patients.”

“The great thing you both were doing the same with more or less success was that, in this terrible situation, you were looking for a point of common ground – who he is, what would work for him, how does he understand that it works,” said Golan, noting that it was important to demonstrate to the patient that they respected his belief system. “The second time you’ll have an AIDS patient like him, it will be easier.”

The third scenario the students faced was perhaps the most challenging – a haredi woman named Ruti was experiencing bleeding between periods and was convinced that this was a punishment for something bad she did in the past.

After hearing Ruti say, “I did some very bad things when I was little,” Namita Rokkam, 25, asked her why the bleeding began now rather than a long time ago. But she would only answer, “Because I have a bad thought – I am thinking about bad things,” and then mentioned that she needed to protect her daughter, with no further explanation.

The students actually were never able to uncover what the “bad things” actually were, but Rachel Dunham, 24, was able to get her to speak about her childhood and her family relationships – discovering that her bond with her five sisters had always been strong but only receiving muted grunts at the mention of her five brothers. “I tried talking to my mother but she didn’t listen,” she said, but ultimately wouldn’t talk to the doctors.

The students ran out of time before they were able to get any farther through Ruti’s seemingly impenetrable wall, causing the actress to later tell them, “I didn’t feel that you really tried to come close to me.”

Despite the frustrations they experienced, the students overwhelmingly thought the day’s experiences were invaluable in preparing them to face real-life clinical situations in environments that might be less than friendly to their Western, English-speaking approaches to medicine.

“I definitely enjoyed the chance this morning to hear pieces of people’s cultures from the class and I think it worked,” Dunham said. “I was just thinking about where we started three years ago – it worked because we trust each other a lot.”