BGU Research May Change Athletics

April 30, 2015

The Jewish Advocate — It is a well-known fact that major tackles in football are likely to cause brain damage, but what about the mild concussions that football players experience as a result of less significant hits?

Using a new and enhanced MRI diagnostic approach, researchers at BGU’s Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience and Soroka University Medical Center, located in the Israeli city of Beer-Sheva, found brain damage following repeated mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI) in professional football players.

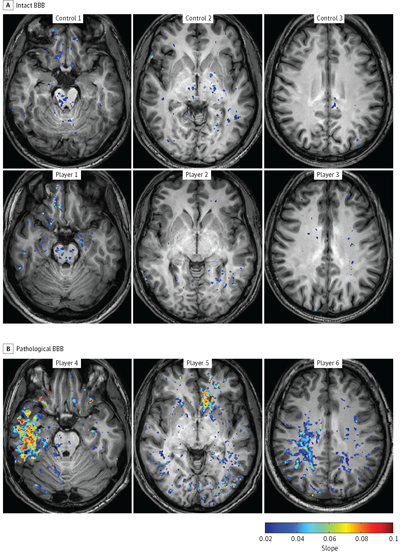

The images from the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev JAMA Neurology study represent Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability in Football Players (A) vs. a control group (B). The players in the pathological-BBB group (B) presented focal BBB lesions in different cortical regions including the temporal (player 4), frontal (player 5), and parietal (player 6) lobes.

Specifically, the scientists saw damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which separates the circulating blood from the brain extracellular fluid, and acts to protect the brain from common bacterial infections.

“Controlling the BBB is kind of a Holy Grail,” said Itai Weissberg, M.D., Ph.D., a researcher in Prof. Alon Friedman’s lab at Ben-Gurion University.

“Maybe we would want it to open after a stroke for three to four days. But no one knows how long it should be opened, when to close, or how tightly to close it.”

Study participants included 16 football players from Israel’s professional football team, Black Swarm, and 13 track and field athletes from BGU who served as controls.

Black Swarm, the Beer-Sheva football team is part of the Israel Football League, which is sponsored by New England Patriots owner and Jewish Bostonian Robert Kraft and his family. Currently in Israel there is only one American football stadium, the Kraft Family Stadium.

Prof. Friedman collaborates on research with Dr. Lee E. Goldstein of the Boston University School of Medicine and College of Engineering, as well as researchers at Dalhousie Medical School in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and UC Berkeley.

The Brain Bank at Boston University collects and studies post-mortem brain and spinal cord tissue of athletes to better understand the effects of trauma on the human nervous system.

American football is not a prevalent sport in Israel and most players pick up the game after they graduate from school, unlike in the United States, where some children start at the age of six. Most players in Israel stop playing soon after they finish college.

When studying Israeli football players, the BGU scientists did not detect brain damage or cognitive impairment using a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine.

However, when using the more advanced system of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE) MRI, they were able to generate more detailed brain maps that showed brain regions with abnormal vasculature, or a leaky BBB.

A BBB leak also appears on brain images of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Results of the study may be extrapolated to understand more about Alzheimer’s disease, which is hard to diagnose and identify, similarly to mild brain injury.

“MRI can show many things. Under normal scans, you see the anatomy of the brain clearly,” said Weissberg, who worked with Prof. Friedman to develop the new imaging method. “But some things do not show up in the resolution of the MRI, if there is no anatomical change yet. What we’re doing is using MRI contrast material. We inject the contrast material and can see it going into the arteries and veins, and then see it disappear. In the normal brain, it’s supposed to go out, but when BBB is dysfunctional, we can see it accumulate.”

Israeli football players were scanned with the DCE-MRIs between games during the season, revealing significant damage. While 40 percent of the examined football players with unreported concussions had evidence of a leaky BBB, only eight percent of the control athletes had similar damage. Clearly, not all the players showed pathology, indicating that repeated, mild concussive events might impact some players differently than others.

Due to the variability in response to mild hits, this new diagnostic tool may be used to determine when a player is ready to get back on the field. “Generally, players return to the game long before the brain’s physical healing is complete, which could exacerbate the possibility of brain damage later in life,” said Friedman.

“To show that these are the players who will get sick, we need to follow players for a long time, show that this is happening to them. That’s why we’re collaborating with Boston, Berkeley and Halifax to get hockey and football players for a larger sample size,” Weissberg explained.

“Ideally, we would like to have long term data on how this correlates to cognitive impairment and psychiatric illness.”