BGU Research Could Determine Football Safety

BGU Research Could Determine Football Safety

May 5, 2015

Head injuries and their potential for long-term brain damage have been a common problem in football. Until recently, it was impossible to tell the difference between harmful injuries and those that are not. A new diagnostic developed at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev explained in this excerpt from Newsweek could change the face of football safety.

Newsweek — Former NFL player Aaron King remembers a hit that left him waking up confused about why his teammates all had worried looks on their faces. It was the first day of football practice at the University of Texas at El Paso. King, fresh off an all-state career in high school, got whacked. “I’ll never forget it,” King says, “because I’d never been hit like that before.”

He went on to play four years of college football, regularly receiving and delivering similar hits. They all hurt, but most of the time he could forget about them. It wasn’t until 2010, as a professional, that he suffered his first officially diagnosed concussion. His second came a year later, and it was followed closely by his decision to leave football forever.

Brain damage has left him with blurry vision in his left eye, and sometimes he sees double. As part of the workers’ compensation he receives from the United Football League, his former employer, he’s been given glasses with corrective lenses, but King says he still isn’t fully healed. He may never be. “You feel like you don’t have access to your entire brain.”

If King’s story sounds familiar, it’s because football has consistently had issues with head injuries at just about every level. For the scientists collecting data hit by hit, scan by scan, the question isn’t, “Is football dangerous?” The real question is, “Can football ever be safe?”

That crucial question can’t be answered yet, because when it comes to traumatic brain injury (TBI), neuroscience still only sees part of the picture. Even the most advanced imaging techniques can’t differentiate between a damaged brain that needs treatment and a damaged brain that can be left alone.

That crucial question can’t be answered yet, because when it comes to traumatic brain injury (TBI), neuroscience still only sees part of the picture. Even the most advanced imaging techniques can’t differentiate between a damaged brain that needs treatment and a damaged brain that can be left alone.

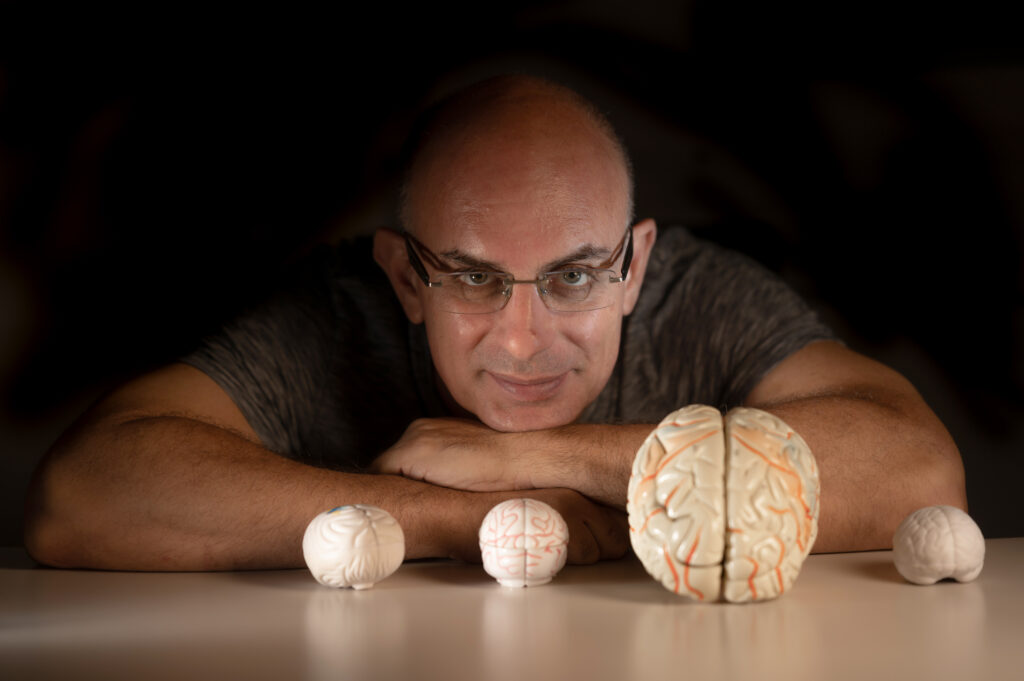

Dr. Itai Weissberg, who studies TBI at BGU’s Laboratory for Experimental Neurosurgery, says the same hit delivered to two players can leave one with partial brain damage and the other unscathed. Figuring out why demands direct observation on a molecular level, an ability that has so far eluded scientists. Fortunately, they may have found a way in.

“Imagine that after a year of playing football we can send kids to a simple MRI scan that will tell which one has a tendency for damage and shouldn’t play,” says Dr. Weissberg. Last year, the BGU researchers published a study, “Imaging Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Football Players,” in JAMA Neurology describing a novel form of dynamic, contrast-enhanced MRI that senses changes in the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a protective layer between the brain and the rest of the body.

In studying 15 football players and 12 track-and-field athletes, BGU researchers found lesions, or openings, in the BBB of six of the football players, but in just one person in track. The most important fact here is that the technique found these disruptions before any physical changes appeared in the brain’s anatomy. The team also found no correlation between BBB damage and concussion history, which underscores research that has repeatedly found concussions aren’t the real culprit in long-term brain damage.

That distinction goes to subconcussive hits that don’t sideline players but leave them the woozier for wear. Scientists know repeated subconcussive hits are damaging, just not how damaging or for how long. Many football players’ greatest risks emerge only after they’ve retired, when other later-age risk factors begin to arrive and bring with them diagnoses of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, ALS and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. But without knowing which hits played the biggest part in triggering these diseases, doctors and scientists can’t take meaningful steps toward prevention.

Dr. Weissberg’s research could change the equation for everyone. If his team can figure out how reliable the BBB is in predicting a player’s risks for more insidious long-term TBI, they could have a real-time brain-damage predicting tool. “After a big hit we [could] scan the player and say, ‘Your BBB is still open, you should rest for another week,’” he says.